In 1970, in “The Female Eunuch”, Germaine Greer memorably wrote that “if you think you are emancipated, you might consider the idea of tasting your own menstrual blood- if it makes you sick, you’ve got a long way to go baby”. We, in the West, are accustomed to thinking of menstruation as largely negative. Hailed as “the curse of Eve”, a part of God’s punishment of women for Eve’s role in the Biblical Fall, blood has been constructed, during the course of the human revolution, to signal inviolability or ‘taboo’.

In an attempt to uncover the usually hidden ‘impolite’ subject of menstruation, artists such as Venessa Tiegs, Ingrid Berthon- Moine and Judy Chicago have expressed a desire to awaken and uncover the usually hidden ‘impolite’ subject of menstruation through its very violation. Broadcasted, the shame becomes a kind of display.

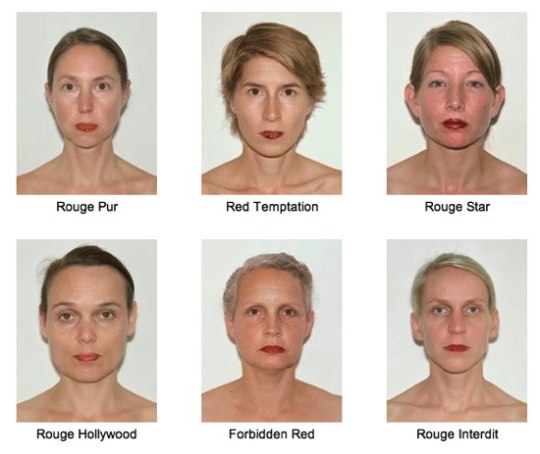

Red is The Colour is a series of 12 portraits of women wearing their menstrual blood as lipstick. Underneath each portrait, each woman is identified with the name of a lipstick commonly found at beauty counters: Rouge Pur, Red Temptation, Rouge Star, Rouge Hollywood, Forbidden Red, Rouge Interdit, Merlot, Red Taboo, La Femme en Rouge, Rouge d’Enfer, Rouge Noir and Action Red. Interestingly, more than half of the women assume ‘foreign’ titles. This ‘foreign-ness’ serves to symbolize the lack of understanding regarding women and their monthly cycle of fertility, a process that the average woman undergoes around 400 times during her lifetime. While menstruation itself has at least a degree of biological regularity, Berthon-Moine’s choice to administer both French and English titles may also be symbolic of the strikingly variable voicings and valences, both cross culturally and within single cultures, menstruation seems to subsume.

The style in which these photographs are presented infer to what has been defined as taboo. By definition, the term ‘taboo’ suggests limitation on behaviour in relation to persons or things believed sacred and/ or polluted and thereby endowed with a dangerous power. Because menstrual blood and monstrous women are perceived as dangerous, taboos have been devised to contain their energies and keep them from spreading beyond a limited place in the order of things. The physical and emotional imprisonment of women is clearly illustrated in Berthon- Moine’s ‘mug shot’- esque photographs. Assuming the same expressionless portrait, devoid of all personality, stripped of all clothing, each female is detached of all identity. What remains is a thing most intimate and personal, the very thing that secludes them from society- their own menstrual blood covering their lips.

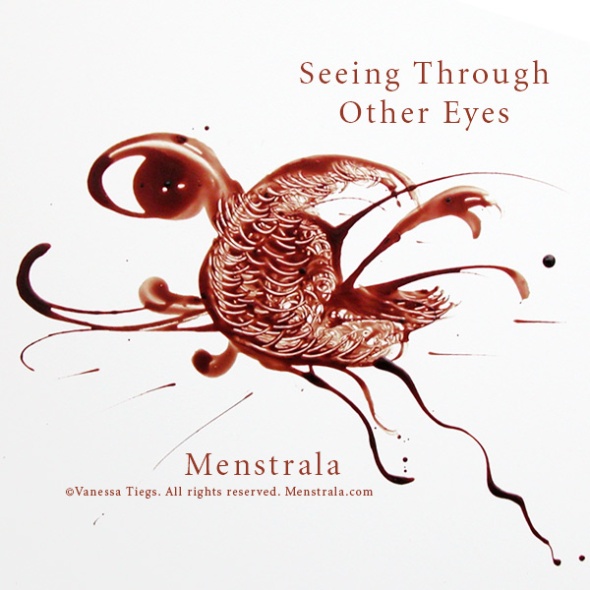

Featuring 88 paintings, “Menstrala” is documentation, as well as a journal, of what the artist, Vanessa Tiegs, has termed “the monthly cycle or renewal”. Astonished at the ignorance and naivety of both women and men in their understanding of the fertility cycle (their knowledge far more eminent and abundant with regards to the cycles of the pay check), Tiegs, like Berthon- Moine, uses her own menstrual blood as a medium to raise awareness and encourage understanding.

In an alternate use of a medium deemed socially taboo, Tiegs paints with her own menstrual blood, not to shock, but rather, in an expression of sexuality, herself, womanhood and the world. In doing so, she challenges the voyeur and their reaction to the blood. The adjective of choice, whether beautiful, dirty, shameful or offensive, depends upon the attitude one has towards the medium, and thus ultimately, to what social environment one has been exposed to.

Within the public sphere, more specifically within the realms of advertising, the lack of visual abet has become intent on obscuring a natural and integral process, instead, marketing it as a societal curse. Where menstrual products usually reside in bathrooms, in the advertising world, according to Ann Treneman, author of ‘Cashing in on the Curse: Advertising and the Menstrual Taboo’, “they never seem to get near the porcelain”. It is unthinkable to show them being used. Where clear instructions and simple visual aids purposely market the removal of (male) facial hair with the latest razorblade, never has the tampon been administered with its instructions of ‘how to’. Thus, advertisers see themselves plunging tampons into clear water to prove their points on absorbency. The colour red seems forbidden- blood must not even be suggested, let alone actually mentioned.

Although the irony is not lost in the customary use of a female voice to sell “shame” to women, advertisements are meticulously placed, restricted even, to within the vicinity of the female gaze. In doing so, they keep within the limits of the societal belief that menstruation is for a woman’s eyes only. Again, Treneman writes, “perhaps the ultimate irony of menstrual advertising is that it seeks to instill a desire to erase the very thing the product is designed to service”.

Feminism has always been deeply concerned with questions about representation, with the politics of images- a concern with the way ‘woman’ has been used in male representation and with woman’s relegation to a marginal area of culture, specifically excluded from ‘high art’. Art, albeit more liberal contemporarily, is still judged by standards where beauty is paramount, where aesthetic considerations create systems of value. Judy Chicago introduces the question of the woman’s body, its place in representation and the female artist’s relation to the woman’s body in representation. Famed for works such as “Red Flag”, “The Birth Project” and “Menstruation Bathroom”, Chicago candidly confronts themes of identity and sexuality.

Chicago, utilises the fears associated with menstruation in order to produce controversial art work- artefacts which oppose the dominant cultural, social, and politically constructed ideals. “Red Flag” illustrates a common place event in many women’s lives: removing a tampon. Yet, Chicago has commented that many people could not identify the red object, some believing it to be a bloody penis, highlighting the unwillingness of both men and women to look at personal, everyday and necessary functions. Whilst there are those who criticise artists such as Chicago, condemning their work as “totally off the wall and pointless”, defenders of the use of ‘tabooed’ mediums (blood, hair, nails etc) speak of the extent to which we are unable to deal with our own humanity.

Although it has been female artists, namely, Chicago, Berthon- Moine and Tiegs, that have come to emphasise the importance of menstruation, male artists such as Marc Quinn and Piero Manzoni have also caused controversy within the public sphere, using both their own blood and ‘shit’ as mediums with which to question conventionally accepted meanings. The human body, for them, becomes a canvas- a tool or weapon of domestication and disciplination and of identification, subjection and resistance.

The drive to violate taboos is an essential impulse in modern culture. Using the medium as the message, they want us to stop staring and start tasting.